Moving Food Safety Forward

When Max Wamsley walks into a room – or a research lab – you quickly realize he is not just another chemist. A PhD-educated optical spectroscopy and measurement science expert, an Army research chemist and the founder of an emerging biotech startup, Wamsley navigates the worlds of science, business and entrepreneurship with equal parts curiosity and grit.

He is also a proud Mississippi native, a soon-to-be MBA graduate from Mississippi State University and a man on a mission to transform how we measure food quality, starting with pet food.

Hailing from Vicksburg, MS, Wamsley completed his undergraduate degree in biochemistry, with a minor in computer science, at Centenary College of Louisiana. His passion for measurement science and chemical instrumentation brought him to Mississippi State, where he earned a PhD in chemistry and found a campus community deeply rooted in innovation.

“I chose MSU because I wanted to do chemical instrumentation, and they had strong funding and faculty in that area,” he explains. “I visited during COVID, and even with limited options, I knew it was where I needed to be.”

Now, Wamsley is pursuing his online MBA from Mississippi State and is on track to graduate in December 2025. But he’s already applying those business skills in real time as the founder and CEO of Clarus Labs LLC – a startup rooted in his doctoral research that is gaining serious momentum.

Clarus Labs was born from an unassuming research challenge. A fellow professor approached Wamsley’s advisor, Dr. Dongmao Zhang, with a question: Could Zhang’s lab improve a dated and unreliable method for measuring meat oxidation, an issue of concern to the meat and pet food industries?

What began as a methodological problem quickly transformed into a broader opportunity.

“We started improving the test, and we realized we could develop a portable, cost-effective instrument that could be used on-site in supply chains,” Wamsley says.

While Zhang, a professor in MSU’s chemistry department, chose not to pursue the commercialization route himself, Wamsley says his mentorship and technical guidance were instrumental.

“Dr. Zhang built the foundation, and I’m standing on it,” he says. “We wouldn’t be here without him.”

Backed by National Science Foundation, or NSF, and National Institutes of Health funding, the research eventually caught the attention of the NSF’s Small Business Innovation Research program. Clarus Labs applied for a federal grant through the NSF’s Seed Fund, which, if awarded, could provide up to $1.5 million in startup funding.

“We’re past stage one of the review,” Wamsley exclaims. “That alone is a huge step forward!”

At its core, Clarus Labs’ innovation improves upon oxidation testing, which is a way to measure how rancid, or chemically degraded, a meat product has become. The current testing methods, dating back to the 1940s, can be unreliable, time-consuming and require advanced chemistry training.

“Traditional tests can take eight hours and require extensive sample prep,” Wamsley explains. “If you mess up one step, you have to start over. Our method is faster, simpler and more reliable. It’s a three-step process: blend the meat sample, filter it and drop it into our reaction solution. The portable instrument does the rest.”

The result? Reliable data in less than 10 minutes, with accuracy across various types of meat – including beef, chicken and now pet food.

Although the technology was initially developed for poultry applications, Wamsley and his team quickly discovered a more urgent market: the pet food industry.

“Pet food often uses older meat, and quality varies a lot,” he says. “There’s no current quick method to test the oxidation level of the ingredients before they’re processed. Our test fills that gap.”

The need is real. Many companies currently rely on visual inspection or slow, lab-based methods that are not scalable. With Clarus Labs’ tool, pet food manufacturers could test ingredient quality upon delivery – even before unloading – saving time, money and, potentially, animal health.

Wamsley points out the possible long-term health benefits as well.

“We don’t currently check pet food quality the way we do for humans,” he remarks. “But some of these oxidized compounds are known to be carcinogenic. If we can screen for them in ten minutes, why wouldn’t we?”

While Wamsley leads Clarus Labs, he also works full time as a Research Chemist for the U.S. Army Development Command Chemical Biological Center in Maryland, a position he accepted after completing his doctoral studies through an Army scholarship program.

“I’m gaining experience in bacterial detection and biochemistry, which could open up new applications for our technology down the road,” he says. “It’s tough balancing both roles, but the work aligns in exciting ways.”

To better prepare for the business side of leading a startup, Wamsley enrolled in Mississippi State’s online MBA program, supported through a scholarship connected to the College of Business and the Thad Cochran Mississippi Center for Innovation and Technology, better known as MCITy, a startup incubator in Vicksburg.

“As a scientist, I knew the chemistry,” he says. “But launching a startup requires a different language – accounting, supply chain, business strategy. Earning my MBA at Mississippi State has helped bridge that gap. I’m learning in real time how to make Clarus Labs viable long-term.”

As part of his teaching assistantship through MCITy, Wamsley supports small businesses at MSU by helping them develop business proposals. He also writes grants for Clarus Labs as part of his formal duties. That hands-on experience has been integral to both his academic and entrepreneurial growth.

His path from researcher to entrepreneur was not always smooth. Learning to navigate startup operations, customer discovery, funding strategy and regulatory hurdles came with steep learning curves. That is where the MSU College of Business, the Center for Entrepreneurship and Outreach – known as the E-Center – and MCITy played pivotal roles.

“I’ve had incredible mentors, especially Nick Pashos at the E-Center and Tasha Bibb with MCITy,” says Wamsley. “I also completed the NSF I-Corps program and interviewed more than 160 potential customers to understand the market.”

COLLEGE OF BUSINESS | MISSISSIPPI STATE UNIVERSITY 2025-26 | DIVIDENDS 37 Despite working in Maryland, Wamsley says he is committed to keeping Clarus Labs rooted in Mississippi, specifically in his hometown of Vicksburg.

“MCITy is doing great things for economic development,” he says. “I want to hire local talent and collaborate with all Mississippi universities. My long-term vision is a thriving company that stays in the state and helps build its innovation ecosystem.”

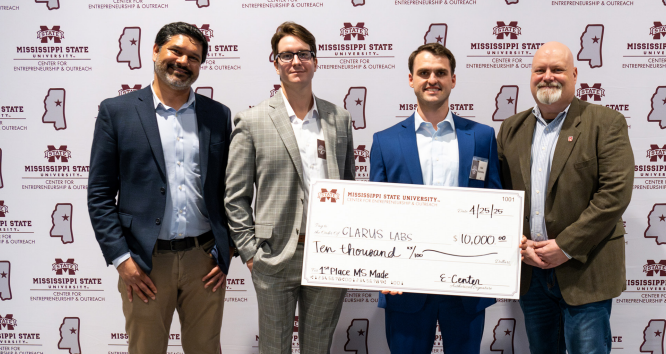

That commitment was on full display at MCITy’s Dawg Tank pitch competition in June, where Clarus Labs took second place. The previous spring, Wamsley took home the $10,000 grand prize in the Mississippi Made category at Mississippi State’s 2025 Startup Summit. He says he plans on using those funds to support additional research at MSU by funding a research assistant in his former lab. The research assistant will focus on introducing a new chemical for their testing technology.

“We measure what’s called ‘secondary oxidation,’” Wamsley explains. “Basically, when meat degrades, it first breaks down into one chemical – this is called primary oxidation – and then into a second one, which is secondary oxidation. A lot of the food industry wants to measure that first step. What we’re trying to do is get the technology working for both stages of the degradation process, which would open the door to broader applications in the future.”

The road ahead for Clarus Labs includes refining their portable instrument, developing user-friendly software and potentially attracting investors to speed up commercialization.

“Currently, the software is somewhat of a bottleneck,” he says. “I could write it, but I honestly don’t have the time. We’re hoping to bring on a software specialist or find investment to scale faster.”

Broader applications beyond pet food are also on the horizon – think oxidation testing for sauces, chips and potatoes, as well as potential use in Department of Defense settings for environmental or illicit substance detection.

Even amid these ambitions, Wamsley remains humble – and grateful.

“I may not be the smartest person in the room, but I do work hard, and I ask for help when needed,” he says. “That’s what’s made the difference.”

To students and researchers dreaming of launching their own startups, Wamsley offers clear advice: “You’ve got to love what you’re doing, or you won’t have the stamina. And if you don’t want to be the CEO, that’s fine; find someone who does. Just don’t let the idea die if you believe in it.”

He also stresses the importance of relationships.

“Build your network,” he adds. “Every connection could help you down the line. Whether it’s faculty mentors, classmates or someone you meet at a conference, stay connected.”

With his passion for science, determination to improve food quality and a growing base of support across institutions and industries, Wamsley is poised to make Clarus Labs a success story born from research – and rooted in Mississippi.

By Emily Daniels